2019 : The End of Filmy Love Story

2019 : The End of Filmy Love Story

The momentous journey of Romantic films in Hindi cinema that begun in 1960s after now losing its steam has had interesting social trends guiding the success and failures on the box-office

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Success stories are good to delineate

emerging trends during the year. But there also failures that enunciate a big

story.

Pal Pal Dil Ke Paas hardly

made any mark at the Box-office. However, for those searching for

successful ideas at the Box-office, it did make a mark. PPDPK’s performance

beguiled the end of an era in Hindi cinema that had gained momentum in 1960s.

Romantic films have been charting

success stories since 1960s. Their success ratio became so high that love story

became the de facto launch theme for star kids (Rishi Kapoor, Kumar

Gaurav, Sanjay Dutt, Sunny Deol, Amir Khan). Even proven actors like Kamal

Hassan chose not to risk other themes.

No wonder, amongst the most

recommended Hindi films on the internet, the share of romantic films is 40-50%

for films released during 60s, 70s and 80s. For 90s, this figure is even higher

at 70%. It falls to about 25% for 2001-2019 releases. Not surprisingly, average

annual production of romantic films has come down from 20-25 (during 60s-90s)

to 8 in 2018 and to 5 in 2019.

Films reflect societal trends and

vice versa. In Indian society, during 50s, love story was largely an abstract

concept talked about only in folklore

and mythology (Heer Ranjha, Laila Majnu,

Dhola Maru, Nala Damayanti et al). In real world, romantic relationships

existed only post-marriage.

Post-independence, spread of girl

education meant young boys could interact with young girls and thus were able

to find someone that they could better connect with than someone within

their own community (as was the prevailing practice then). But 60s, 70s, and 80s

was still an era when “girl friend” was yet a hush-hush word. Moreover, large

part of the society was not open to inter-community bonding. Therefore, most of

these affairs, got restricted just to the dreams and aspirations of youth. And

cinema being a place for expression of unfulfilled desires, it was here that

the youth could experience romance which in real life they could only yearn for.

Romantic films, hence, became an instant hit.

But since in real world, unsuccessful

love stories far outnumbered successful ones, audiences in larger numbers would

emotionally connect with the doomed lover. So doomed love stories charted

bigger box-office success

“Maine jaanta hoon ki tu ghair

hai magar yoon hee….Kabhi kabhie mere dil mein khayaal aata hai…”,

These lines would so well connected

with millions of failed lovers. So then came, love triangle which presented a

terrific combination of emotions of failures in love, of those struggling in

their love and of those successful in love ; making it another super successful

plot.

Amidst this struggle for love,

came the epoch-making change brought about by Maine Pyar Kiya (1989). While its famous dialogue, “Ek ladka aur ek

ladki kabhi dost nahin ho sakte” represented the 80s’ culture but it was also

the first time that audiences saw mother’s approval to son’s love story despite

father’s opposition. This portended a big change ; as the Indian middle class moved from a united

opposition to a divided opinion on their progeny’ love affair.

1990s, thus, saw opening up of floodgates

for love marriages in the Indian middle class. Successful love stories started

blooming across Indian middle class. And nothing sells like success. Success of

love stories in real world proved manna for the filmmakers in 1990s. Thus,

romantic films form an overwhelming 70% of the most recommended films of 90s. (Aashiqui,

Saajan, HAHK, DDLJ, Dil to Pagal hai, HDDCS,

Pardes, Mohabbatein, K2H2, KNPH).

In the new millennium, love

stories started blooming across college campuses, across streets, mohallas, chawls

and jhuggies. And as love stories became more commonplace and as parental and

community opposition became minimal, scriptwriters were left with no meat for

an exciting plot. So much so that nothing much aspirational remained about having

a love story. And now, we have reached a

time where a section of youth considers having a relationship not even a necessity, forget

being an aspiration.

Now the question that people I

know will ask me is when love no more remains aspirational, how does a love

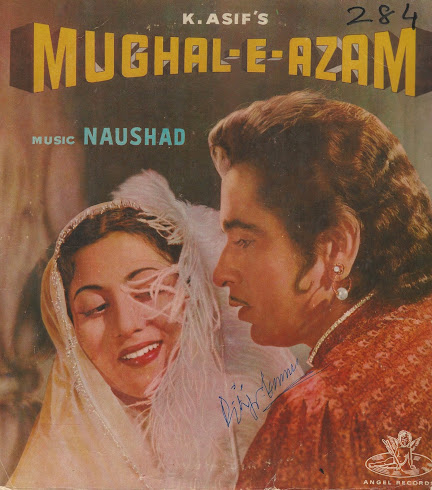

story like Mughal-e-Azam still connects so well on stage. While there

are multiple justifications but the one that I feel is most appropriate is based on what I gathered from a very learned and senior

political leader. He said, “While

analysing a foreign country for diplomatic relations, we observe their theatre

and not their cinema. Reason being, cinema talks about citizen’s aspirations

but it is the theatre that depicts country’s culture and intellect.” Essentially, as format changes, the audience

expectations from the same story would change. In 1960, people saw Mughal-e-Azam

for aspirations, today on stage they watch it for culture.

As format shifts, audience

expectations and as OTT starts dominating content distribution, content

consumption will increasingly become a solo activity than a family activity (as

was during 60s to 90s) or a couple affair ( as is currently in multiplexes) ;

and this only means stories and story-telling need to be reworked.

With Indian young ones putting a

question mark on the need to have relationship, it is only logical that

romantic films may see a full stop. But, it is also true that only after a full

stop begins a new para. May be today’s love story is not about being pal pal

dil ke paas but about being in a long distance relationship.

Comments

Post a Comment