In Search of Villain

“OTT may kill the business of cinemahalls” was cabinet minister Piyush Goyal’s observation during last fortnight's FICCI Frame’s virtual event.

Experts would most likely have consensus on the above prognosis. But if the same question was reversed, “What can bring back audiences back to cinemahalls ( post the Covid crisis) ?”, consensus would most likely remain elusive. However, in a country with limited options for Out-of-the-Home entertainment, a high youth population and a growing economy, it would only raise one’s eyebrows when one learns that cinemahalls are expecting reduced ticket sales.

The answer to this strange paradox, therefore, lies not in economics or in statistics. It has more to do with fleeing away of that core magnet that has over the years brought audiences to cinemahalls. And this core magnet is not about entertainment value that cinemahalls offer but about the vicarious pleasure that viewing in cinemahalls has provided over the years.

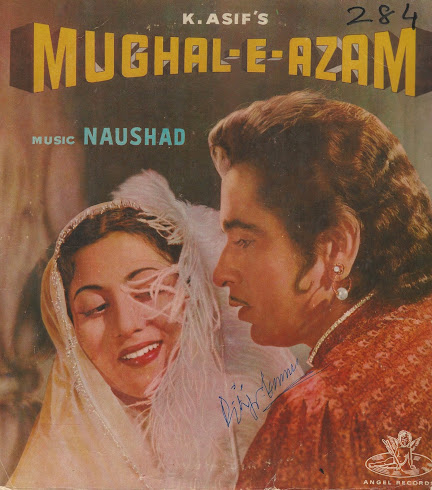

In the India of 40s, 50s and 60s, a big source of vicarious pleasure for the cinema audience was the on-screen exhibition of social justice. A farmer’s battle against a brutal zameendar or workers’ fight for fair wages or a daughter-in-law’s struggle against a cruel mother-in-law would provide a platform to the audience for manifestation of their angst against the villain in the society.

As time progressed, the source of common angst shifted and accordingly the star status moved from the fighters for social justice - Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor, to the warrior against the unfair establishment - Amitabh Bachchan. Yet, the underlying phenomenon that created stars remained the same which was ‘Presence of a Villain’. Even love stories that made many other stars almost always had a villain.

Whatever the form of villain - zameendar, ganglord, mill owner, future father-in-law et al, he would typically be the representative of atrocities or of excessive consumption (of wine, women, wealth). With immoralities or criminality or both on his sides, villain would easily classify as the punching bag for common angst of the audience. The hero then represented the polar opposite – he was righteous and would distance himself away from consumption & wealth (typically would also be from a poor or a middle class family)

As time progressed, the hero in 90s became wealthy and consumption ceased to be a bad word for him. Righteousness was also on the wane, so the frivolous Raj (SRK) could dupe an honest shopkeeper into believing his late night urge for liquor as an urgent need for medicine and yet would be seen by the audience as a hero and not as a villain. The serious Raj (as Raj Kapoor) or the serious Vijay (as Amitabh Bachchan) could never have engaged in such unrighteous and frivolous behaviour. Later, Salman Khan took the frivolousness factor to a new high and got even larger following. Moreover, Chulbul Pandey – the cop, could even engage in crime, take bribes and yet don the hero’s hat. Immorality and consumption now had become acceptable traits of the hero.

Therefore, over the period, the hero in Hindi cinema has expanded his territorial claims and seized away traits like excessive wealth, consumption of liquor and even engaging in petty crimes from the villain. This encroachment by hero has left little scope for filmmakers to define the villain. And, in absence of a clear definition of villain, mobilising audience’s minds for a public revenge against a common villain has become extremely challenging for filmmakers. In the past, it was through the crafted use of villains that makers could make cinemahalls a platform for manifestation of such public aspirations. And this fulfilment of common aspirations was the core magnet that provided audiences with the vicarious pleasure which would otherwise remain elusive in the real world. The vicarious pleasure from spewing of public angst, in the current times, now also has an alternative platform in the form of social media. And lastly, love stories – the evergreen on-screen aspiration and a safe platform for creation of villain, now no more remains a magnet, as Happy Married Life itself ceases to be an aspiration for many a youth.

With drying away of options, filmmakers may have to do rethinking towards creation of stars. Because whether one likes or not, stars do bring audiences to cinemahalls. And the critical link in creation of stars is creation of villain. Good and Evil, as the eastern mystics say, are extreme parts of the single whole – which in simple English means, north pole cannot exist without a south pole. Can we, therefore, expect the makers of Hindi cinema to be able to create new villains ? Heroes, after all, do not exist in isolation.

So true, and that’s why perhaps all the disney, dc, marvel superhero movies are constantly getting in the audiences and especially The younger ones, as their story remains on the standard narrative of hero and villain, good and evil....with a fairly clear distinction between the two.

ReplyDeleteInteresting observation Pat. Based on the same logic, for aeons, David v/s Goliath story has remained a success formula.

Delete